After we buried the ashes of St. Benedict’s Wilfrid, our 10-year-old Airedale Terrier, I was horrified to see our new puppy, a 10-week-old Goldendoodle, digging up the ashes and rolling in them. What at one moment I found disturbing, the next moment I found rather amusing if not fitting. In the strangest of ways, I believe that this big-hearted Airedale Terrier was passing on his Benedictine ways of spiritual direction to Byron, the new Goldendoodle in our life.

After we buried the ashes of St. Benedict’s Wilfrid, our 10-year-old Airedale Terrier, I was horrified to see our new puppy, a 10-week-old Goldendoodle, digging up the ashes and rolling in them. What at one moment I found disturbing, the next moment I found rather amusing if not fitting. In the strangest of ways, I believe that this big-hearted Airedale Terrier was passing on his Benedictine ways of spiritual direction to Byron, the new Goldendoodle in our life.

Ten years before this event, I was ending my first sabbatical at the Collegeville Institute at St. John’s University and Abbey. Many friends of the Institute had named their children or pets after Father Killian O’Donnell, the resident elderly poet and revered monk. But I found that no one had named anyone after Brother Wilfrid, the Institute’s liaison to the Abbey, and when this goofy Airedale pup looked up at me, I knew just then that his name would be Wilfrid, St. Benedict’s Wilfrid to be exact.

Several years later when I returned to the Institute for a summer conference on religion and science, I visited with one of the participants whose wisdom I had grown to trust. Dawn Adams was a Choctaw Indian and one afternoon on a long walk we talked about our relationships with animals. She smiled when I told her that I was considering becoming a Benedictine Oblate or finding a Benedictine spiritual director. I had also mentioned Wilfrid’s strange habit of sitting on the deck each night for about 20 minutes, as he smelled the world into his being.

“You don’t need to become a Benedictine Oblate,” Dawn said to me. “You have a Benedictine creature in your own home and you aren’t even listening to him. Pay attention to Wilfrid. He can be your spiritual director.”

And so it began: my new relationship with a canine spiritual director of Benedictine descent. In those days that followed, I knew that his careful, quiet way of paying attention to the world was exactly what I needed to do for myself. So, every evening, Wilfrid and I would sit in our respective places. Wilfrid sat upright on the deck and I relaxed in a wicker chair. He smelled the scent of the German Shepherd who lived across the fence. Wilfrid looked intently at the branches on the evergreen tree, and he felt the touch of my hand on his back. I gazed at the deep blue of the evening sky, took in the aroma that lingered from the neighbor’s barbecue, and heard the chirping of the sparrows in the nearby bushes.

About 10 years later when Wilfrid developed bone cancer and I could no longer help his pain, I knew I had to part with this King of the Terriers, this wily Airedale. On his last day, when we took him to the vet, I held him in a blanket on the floor and watched him draw his final breath. I began to cry harder than I had ever cried. Wilfrid taught me about unconditional love and how to live in the power of the present moment. As his spirit vanished that day, I knew he had led me to a deeper knowledge of my humanity, my spirit. We had a special bond, canine and human; we parted as spiritual companions.

I knew I couldn’t live without another dog and so Gary, my husband, and I soon found Byron, the reddish curly haired Goldendoodle, who was one of the naughtiest and smartest pups I had met. On that afternoon, when Byron dug up some of Wilfrid’s ashes and rolled in them, I sensed that Wilfrid had passed on the duties of spiritual direction to this new canine of mine.

Byron knows how to play, how to hang out, and how to get what he needs. That canine knowledge and skill turned out to be exactly what his human needed. So, he and I have developed a different spiritual relationship, not one that leads us to sit and gaze at the night skies, but one within which we romp and laugh and play. Byron knows that I long for levity and joy. I don’t always realize this when I have once again become obsessed with grading papers or mastering the hundred new apps on my smartphone. But Byron does. He comes along with that big, wet, black nose and jams it in my arm to let me know, indeed, it’s time for some spiritual direction. And I listen.

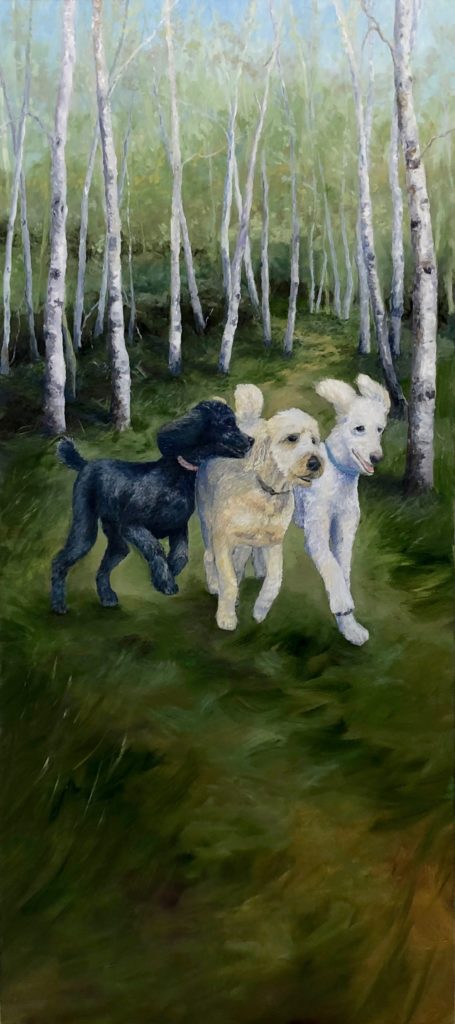

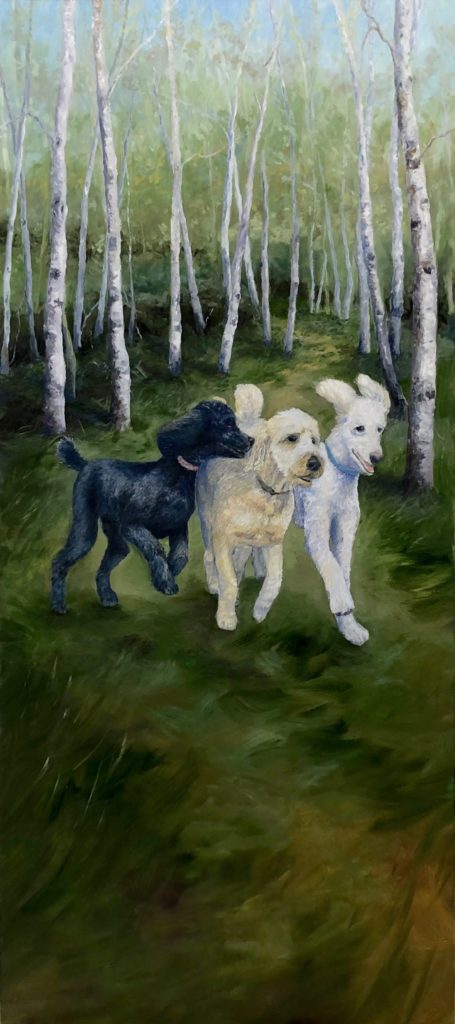

Listen to Dogs, by Gary Pederson, a 3-Part Invention inspired by our three dogs running and fighting playfully.

And the verses wouldn’t go away. This lesson isn’t for me, a new lesson. I have heard it before. I recall what Dawn Adams, a Choctaw woman, said to me years ago. She told me to listen and learn from my Benedictine canine spiritual director. The Spirit of the verses revealed Herself to me in the joy I have when I read the words. The animals, the birds, the plants, and the fish teach me and guide me. All of those non-human creatures were, like me, breathed into being by the life of the Spirit.

And the verses wouldn’t go away. This lesson isn’t for me, a new lesson. I have heard it before. I recall what Dawn Adams, a Choctaw woman, said to me years ago. She told me to listen and learn from my Benedictine canine spiritual director. The Spirit of the verses revealed Herself to me in the joy I have when I read the words. The animals, the birds, the plants, and the fish teach me and guide me. All of those non-human creatures were, like me, breathed into being by the life of the Spirit. “My father was very sure about certain matters pertaining to the universe. To him all good things–trout as well as eternal salvation–come by grace and grace comes by art and art does not come easy.” Norman Maclean, A River Runs Through It

“My father was very sure about certain matters pertaining to the universe. To him all good things–trout as well as eternal salvation–come by grace and grace comes by art and art does not come easy.” Norman Maclean, A River Runs Through It This year I’m learning to see through the eyes of visual artists. Seeing is like listening: both are active practices. I realize how passively I “look” at the world, instead of actively “seeing” with the world. On a warm, sunny afternoon in April, I sat in on a class of art students who had come to work on their projects. The three women, about my age, arrived at the studio with their sandwiches, art supplies and their eagerness to create. Each artist painted on a large, door-sized canvas, producing their view of the South Dakota prairie: sunflowers, cornfields, a sunset in the Black Hills.

This year I’m learning to see through the eyes of visual artists. Seeing is like listening: both are active practices. I realize how passively I “look” at the world, instead of actively “seeing” with the world. On a warm, sunny afternoon in April, I sat in on a class of art students who had come to work on their projects. The three women, about my age, arrived at the studio with their sandwiches, art supplies and their eagerness to create. Each artist painted on a large, door-sized canvas, producing their view of the South Dakota prairie: sunflowers, cornfields, a sunset in the Black Hills. When they run and play, the three dogs know exactly how to move in a synchronized dance of delight. Brindle, a gray Standard Poodle, leaps with a lightness to her being as she bounds across the field. As the youngest of the dogs, she can outrun and outplay both of her senior male dog friends. Jack, a buff-colored Standard Poodle and bigger than Brindle, chases her in large circular movements, arcs of flying dog. Byron, the overweight Goldendoodle, lumbers straight at them, knowing it’s the quickest means to an easier end, flopping down and chewing a knotty brown branch from the bur oak tree. At first Brindle ignores Byron’s posture on the ground and grabs his long tail in her mouth and yanks as hard as she can. Byron rears up and chases after her. For a while. Within moments Jack joins the two and soon the three are spinning, chasing, and biting each other in a whirlwind of motion. Finally, Jack and Brindle shove Byron to the ground as he wears out, his old joints tired. He’s always been a lazy dog, more content to chew a stick than chase it. These three canine friends know each other intimately: every smell they take, every move they make, they simply love to be together.

When they run and play, the three dogs know exactly how to move in a synchronized dance of delight. Brindle, a gray Standard Poodle, leaps with a lightness to her being as she bounds across the field. As the youngest of the dogs, she can outrun and outplay both of her senior male dog friends. Jack, a buff-colored Standard Poodle and bigger than Brindle, chases her in large circular movements, arcs of flying dog. Byron, the overweight Goldendoodle, lumbers straight at them, knowing it’s the quickest means to an easier end, flopping down and chewing a knotty brown branch from the bur oak tree. At first Brindle ignores Byron’s posture on the ground and grabs his long tail in her mouth and yanks as hard as she can. Byron rears up and chases after her. For a while. Within moments Jack joins the two and soon the three are spinning, chasing, and biting each other in a whirlwind of motion. Finally, Jack and Brindle shove Byron to the ground as he wears out, his old joints tired. He’s always been a lazy dog, more content to chew a stick than chase it. These three canine friends know each other intimately: every smell they take, every move they make, they simply love to be together.